Sand, water, and change: documenting the dynamics of a dryland river floodout zone in the Indian Thar desert

Jayesh Mukherjee and team from Aberystwyth University reflect on a postgraduate research (PhD) project undertaken along the ephemeral Luni River in the Indian Thar Desert, funded by the BSG and other organizations (listed at the end).

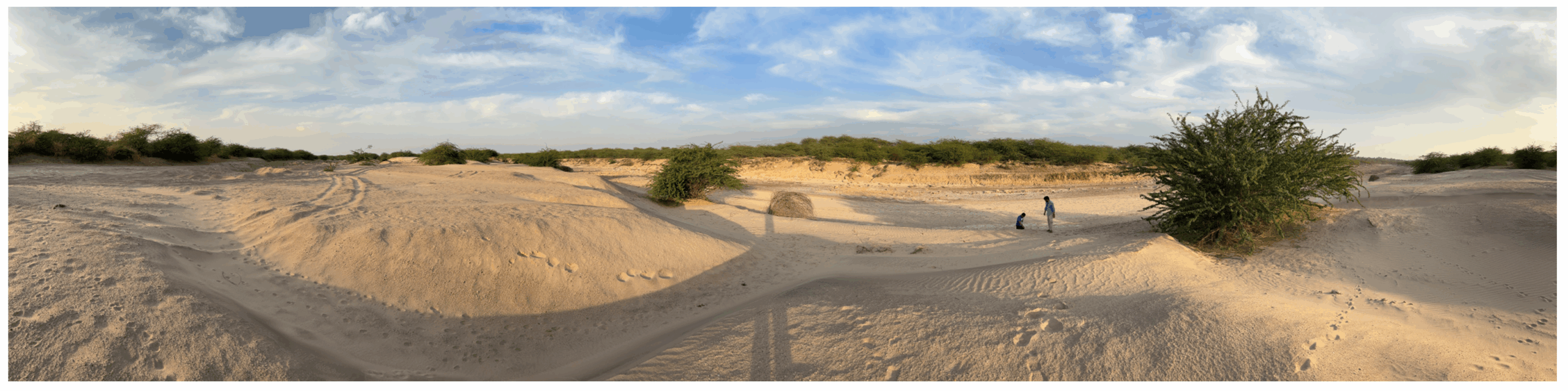

Panoramic view of bars and dry channel from the lower Luni River near Bhukan village (Sindhari tehsil, Barmer district, south Rajasthan). Picture credit: Stephen Tooth.

Geomorphological fieldwork is not only about scientific data collection but also involves an element of exploring and feeling an unknown landscape. The monsoon-fed Luni River begins its lengthy voyage from Govindgarh village, southwest of Ajmer city (eastern Rajasthan). Here, there is a confluence of two headwater streams: Sāgarmati rises from the Naga Hills of the Aravalli Ranges and Sārsutī is sourced from the sacred Pushkar Lake. The Luni River traverses more than 500 km and culminates at one of the world’s largest salt flats (playa), the Rann of Kutch (or Kachchh) in northern Gujarat. The name of the Luni descends from the ancient Sanskrit terms ‘Lavanavāri’, ‘Lonavāri’ or ‘Lavanavāti’ that mean ‘salt river’, and is also locally known as ‘Marugāṅgā’, meaning ‘Ganges of the desert’. The water of Luni gradually turns brackish after it crosses through the town of Balotra (middle course) and approaches the dune fields downstream. We undertook our desert odyssey within the arid expanse of Barmer and Jalore districts of southern Rajasthan in the lower course where the Luni River bifurcates into several anabranching and distributary channels and forms an approximate 60 km long floodout zone adjoining the southeastern margin of the Indian Thar Desert.

Floodout zones form along the low energy, terminal reaches of ephemeral rivers and can be found in different dry (hot and cold) climatic zones worldwide, including Australia, Bolivia, Botswana, USA, South Africa and other parts of India. The recent field visit of our team to the floodout zone of the Luni River included hunting for palaeochannels based on digital elevation model (DEM) results, summitting dune fields, and taking a close look at salt-crusted soils and brine pools to reveal tales that no satellite imagery can adequately capture.

The fieldwork involved driving many hundreds of miles for five days, starting in the early morning and ending at dusk. We navigated through some remote areas, got our vehicle stuck on sandy tracks, and got lost on roads. Even Google Maps failed us at times. But we steadily collected sediment samples for geochronology (Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating), micromorphology (samples to be observed under Scanning Electron Microscope or (SEM)), and geochemical analysis from the various landforms of the Luni’s crisscrossing anabranching and distributary networks, and from flanking linear dunes to try to unveil the ‘landscape memory’. Ancient fluvial activities are etched like scars across the floodout zone in the form of palaeochannels, which are potential ‘geoarchives’. Strategizing sampling locations was quite challenging but careful selection will help us to decipher periods of river aggradation and abandonment, critical for understanding past monsoon variability and how the fluvial system has shrunk since the heyday of the mid Holocene. While we had pre-identified some locations from Google Earth as having promise – for example, remnants of old meander cut-offs – some locations were inaccessible. Other locations admitted us but the thorny invasive mesquite (Prosopis juliflora, locally called Babool in Hindi) pricked us through our clothes and boots.

Our science communication initiative continued. We recorded some of our field actions on camera and uploaded them to YouTube for wider outreach. Over gratefully received offerings of tea, local farmers helped us to understand a crucial issue of the region: extensive salinization, which has been turning lands white. The current hydrological narrative is dominated by the introduction of Narmada Canal water into the previously ephemeral river system, and this has exacerbated the natural soil salinization process in the area. A network of canals has crept across the area, with the laudable intention of bolstering agriculture, but has inadvertently changed the groundwater dynamics. Local farmers shared how they were overjoyed and had profitable farming during the initial years of the canals (early years of the last decade). But a grim scenario has developed, as many lower lying farmlands, especially towards the lower reaches of the Luni’s floodout, are now facing shrinking yields and more farm area is being lost due to salinization and salt crusting. Over time, inadequate drainage and waterlogging have raised the groundwater table, mobilizing native salts from the underlying gypsum layers into the root zone. This is leading to crop failure and so to significant livelihood loss. Overdependence on canals has also made communities abandon their traditional rainwater harvesting practices, which has exacerbated their vulnerability. A decline in socio-economic conditions has been initiated, with out-migration (mainly male family members going in search of employment) leaving villages deserted or with an unbalanced gender ratio and age pyramid. Thus, the salinization issue demands immediate actionable policies by local administrations. Encouraging a shift towards rehabilitating indigenous water harvesting structures and revising cropping patterns to include salt and drought tolerant species such as sorghum, pearl millet (locally called bajra), and barley might be a pathway forward.

The drylands of Rajasthan are a palimpsest, with ancient rivers and modern canals coexisting in fragile balance. As we await our results from OSL, SEM, geochemistry and satellite imagery-based mapping, and then attempt to decode the lower Luni’s history, the voices of farmers serve as a stark reminder that a lack of ecological foresight and expensive technological interventions present serious risks for local communities. My PhD study will explore a range of human-environment linkages from the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation to the present-day impacts of modern canal irrigation on local ecosystem services. Fieldwork helps to transform theories into tangible truths by merging the ‘best kept secrets’ of landscapes held in rivers, sediments, dune sands, and dust with the memories and dialogues of local dwellers. Geomorphological insights coupled with grassroot resilience may provide a wise path forward in this unpredictable, rapidly changing world.

Snippets from the fieldwork. In clockwise order from top left: Ephemeral riverbed of Luni’s distributary channel in the floodout zone near Barnwaa village. Collecting an OSL sample from a section of palaeochannel near Goliya Kalan village. Aeolian dune mining (likely for construction sand) near a field site at Berro ka Panna village. Interacting with local farmers near Umarkot village. OSL tube from a trench bottom in a palaeochannel near Malipura village. Narmada distributary canal from Barsal ki Beri village. Salinized stretch of one of the Luni’s distributary channels (also called Little Salt desert) near Janvi village. High saline concentration has poisoned many plants.

Jayesh Mukherjee is grateful for the fieldwork funding support from the British Society for Geomorphology’s Postgraduate Research Grant, the Quaternary Research Association’s New Research Workers Grant, and an AberDoc and President’s Scholarship from Aberystwyth University.

– Jayesh Mukherjee, Stephen Tooth, Manudeo N. Singh and Hywel M. Griffiths from the Earth Surface Processes Research Group, Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Wales, UK. For correspondence: jam169@aber.ac.uk.

~ Edited by Adam Hartley, 3rd June 2025.